Sheila Byfield

Sheila Byfield worked in the media industry for 43 years. Her final role was global Head of Insights and Research at Minsdhare where she managed both industry and proprietary research. She has been a frequent speaker on industry platforms and has a wide range of published work.

She sat on The Media Research Group Committee, was chair of the European Association of Advertising Agencies Research Committee and is a visiting research fellow of the University of Leeds.

Sheila is the author of ‘In with the old. In with the new’ which she describes as ‘a no nonsense approach for communicating with real people in the real world’.

“Whoever controls the media controls the mind.”

There is some debate over who should be credited with this quotation. Some believe that it should be attributed to the American professor Noam Chomsky whereas others are convinced that the words were uttered by the American singer-songwriter Jim Morrison – the frontman for The Doors who were a major rock band in the 1960s.

Talk about going from one extreme to the other but, whichever you believe, there is certainly an element of truth in the sentiment especially when looking at major historical events such as the Iraq war and various elections such as Nixon versus Kennedy and the Tony Blair landslide victory in 1997. Certainly the Murdoch empire believed it had a strong influence. “The Sun wot won it” ran the headline on the day after the election.

Whether the media create or reflect society is also debatable but there is no doubt that media behaviours have changed significantly over past decades. The UK has shifted from a newspaper and broadcast ecosystem to one where public service broadcasters, commercial publishers, platforms and influencers jostle for attention.

Audiences both follow and lead these changes. In 2024 / 2025 Ofcom found that around 96% of UK adults still consume news in some form but access routes have diversified. Now as many as seven out of ten adults consume news online at least some of the time if not exclusively.

From the above examples, we know that media content can influence public opinion but the question remains as to whether changes in media behaviour also have influence. In other words, will opinions be influenced because of the nature of the channel delivering the information?

This essay will use Target Group Index data over thirty-five years to explore the relationship between shifting media behaviour patterns and the attitudes of the British population.

A few words on the Target Group Index (TGI)

The first TGI launched in 1969 and has published wide-ranging data annually ever since from a nationally representative UK sample of 24,000 adults aged 16+.

The data cover detailed category, brand, social, attitudinal and media behaviours all of which can be cross-analysed. The AMSR has secured access to data from 1987 on a rolling basis up to four years ago at any given time. The data for this essay therefore are from 1987 up until 2022 analysed each five years.

Snapshot surveys are useful in studying what people think and do but having such a comprehensive source of information from large samples over extended time periods is immensely valuable indeed.

Twenty four hours is a long time in politics. Thirty-five years is an eternity in the media landscape so how much has changed?

In almost four decades we have gone from fixed phones to mobile, from VHS to YouTube, from encyclopaedia to Wikipedia, from classified advertising to Search, from dial up to always on – and so on.

We have entered an era where the phone is a film studio, FANG (Facebook, Amazon, Netflix and Google) along with Tik Tok and X rule the media landscape. And now we are trying to assess whether artificial intelligence is the answer to all of our prayers or will destroy humanity. To say that our media behaviour has changed as a result of technological developments is an understatement.

TGI data demonstrate shifts in both media behaviour and attitudes.

In 2002 only 3% of the UK population agreed that the first place to look for news is the Internet. Twenty years later the number had risen to almost 40%.

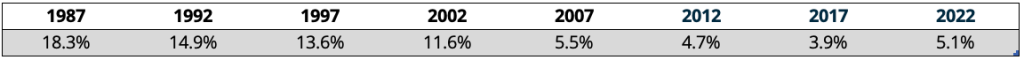

In contrast people’s reliance on newspapers for information moved in the opposite direction:

Newspaper loyalty has suffered too. There was a time when we all knew what was meant by a Guardian, a Telegraph or a Sun reader. These definitions may be a lot less distinct nowadays.

“I would not change the newspaper I read“

% definitely agree

People have always been reticent to confess to liking or paying attention to advertising and rarely agree that it has any influence on their purchase decisions. Even given this bias, advertising is suffering from opinions that are becoming even more negative over time.

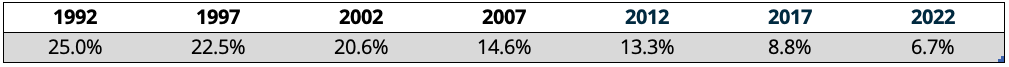

Historical research often tended to suggest that people have a closer affinity with local than national media. This is not surprising as, by definition, they provide news and information of events that are closer to home and will potentially have a greater impact on the recipient than national events. TGI data however suggest that affinity to local media is also suffering a decline.

The TGI database contains a vast array of attitudes outside the media landscape. There is no suggestion here of any causation between media use and other aspects of life however it is interesting to see correlations between them.

It is also worth noting that the most recent data period included here is 2022 which was at the end of the pandemic restrictions. We could be seeing the effects of Covid 19 on quality of life which may account for an increase in negative attitudes.

People worry more.

There is a shift in how people think about now and the future:

The bigger picture

1: TGI – The Reality Checker

“Embrace reality even if it burns you”

Pierre Burge, French industrialist

Whenever new media technologies arrive on the scene, the advertising business is rife with speculation on how our behaviours will evolve. Often these predictions are extreme to say the least.

In the early 1990’s the BBC aired a programme called ‘The Future of Advertising’ and it looked very bleak indeed with scenes of advertising agency offices covered in cobwebs and dust.

Experts appeared throughout the programme predicting the implications of a new, exciting, interactive, television world. Their view on the future of advertising was that it was completely screwed…

“It could be the death of broadcast advertising as we know it… We can’t be sure that ad supported TV will have a future”

Edwin Artzt, (then) Chairman of Proctor & Gamble

“What we are going to see is a total switch in traditional advertising practices… the end of traditional advertising where advertisers will send out messages”

Michael Schrage, (then) media columnist, Adweek

“The viewer becoming the editor rather than the broadcaster is a real prospect indeed… viewers having the power to direct their own commercial breaks”

Rob Norman, (then) media director, CIA

This group was not alone. In 1994, George Gilder published ‘Life After Television’ and told us very confidently that computer and fibre optic technologies spelled out certain death for both television and telephony.

“In coming years, the very words ‘telephone’ and ‘television’ will ring just as quaintly as the words ‘horseless carriage’, ‘icebox’, ‘talking telegraph’ or ‘picture radio’ ring today. Revenues from telephones and televisions are currently at an all time peak but the industries organised around these two machines will not survive the century.”

George Gilder, ‘Life after Television’

It is a sobering thought that the first interactive TV experiments were taking place in the early 1970s and yet now, 50 years later, while it is certainly true that much has changed, we are still not directing our own commercial breaks and advertisers are, by and large, still sending out messages.

The TGI may have provided a useful guide as to what the future held. At around the same time as the BBC programme, only 6% of adults were expecting to watch cable TV at least two days a week and even by 2012 only 4,5% were interested in 3D television and only 5.6% were keen to create a personalised TV programme schedule.

There is a tendency to overestimate the speed of change in the short term and underestimate ifs impact on the long term. However, at the end of the day, it is we the public who will dictate the speed and direction of change. A quick reality check with a large-scale, reliable, representative research survey such as the TGI could have provided a far more realistic view of the future and better advice on where our commercial emphasis should have focused.

2: TGI – The fact checker

In one of his newsletters, Bob Hoffman, The Ad Contrarian, highlighted research conducted by Research Now where 250 people from ad agencies and the marketing fraternity were asked to estimate viewing behaviour on a television versus a SmartPhone. They were shockingly inaccurate.

The ‘professionals’ estimated that 25% of viewing was on a television and 18% on the ‘phone. In the real world the percentages were 82% and 2%. Thinkbox, Radioworks and Ebiquity conducted similar research in the UK in 2018 with very similar results. Once again, the ‘traditional’ channels were underestimated while the newer online alternatives were grossly overstated.

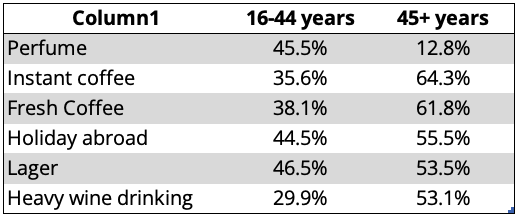

This would be of no importance if it didn’t impact on demographic targeting and channel selection. The advertising and marketing professions tend to be young, urban individuals when both channel and category profiles may not be so biased towards ‘people like us’.

Again TGI can help. There are many categories where one might assume that the profile is young whereas the greatest volume of sales is from older groups. For example:

Conclusions

It is difficult to be conclusive over whether media behaviour as well as media content drives changes in attitudes. Certainly declining trust related to shifting political views have been well documents and those influential messages are largely driven by media vehicles – notably social media.

In the earlier example of the Nixon / Kennedy TV election debate Nixon looked tired and haggard whereas Kennedy appeared fresh and soave. Interestingly, it was mainly TV viewers who shifted opinion in favour of Kennedy. Radio listeners remained largely consistent in their views.

So while it is often difficult to prove correlation, it seems reasonable to assume that behaviour also has influence – in this case radio compared with television.

We have already acknowledged that the speed of behavioural change may have been overestimated in the short-term but it is possible (and probably likely) that its impact will be phenomenal in the long. Certainly attitudes amongst the young vary significantly from the population at large in the world of on-line media. When the youngest groups of today are in an older cohort, their digital behaviour may be more extreme than that of the equivalent age group now.

This means that behaviour and opinions need to be monitored and studied in depth and over time to understand the impact of change and provide better marketing and advertising solutions for commercial operators, their brands and their services.

We are fortunate to have the Target Group Index. It can fulfil all of these core requirements with its historical contexts, large, representative samples and exhaustive coverage of what people think, what they buy and how they behave. It is difficult to imagine a more comprehensive study.